'Silent Hill f' Explained: The Decline of Ebisugaoka

Post-war penury and natural disasters spell the death of this town...

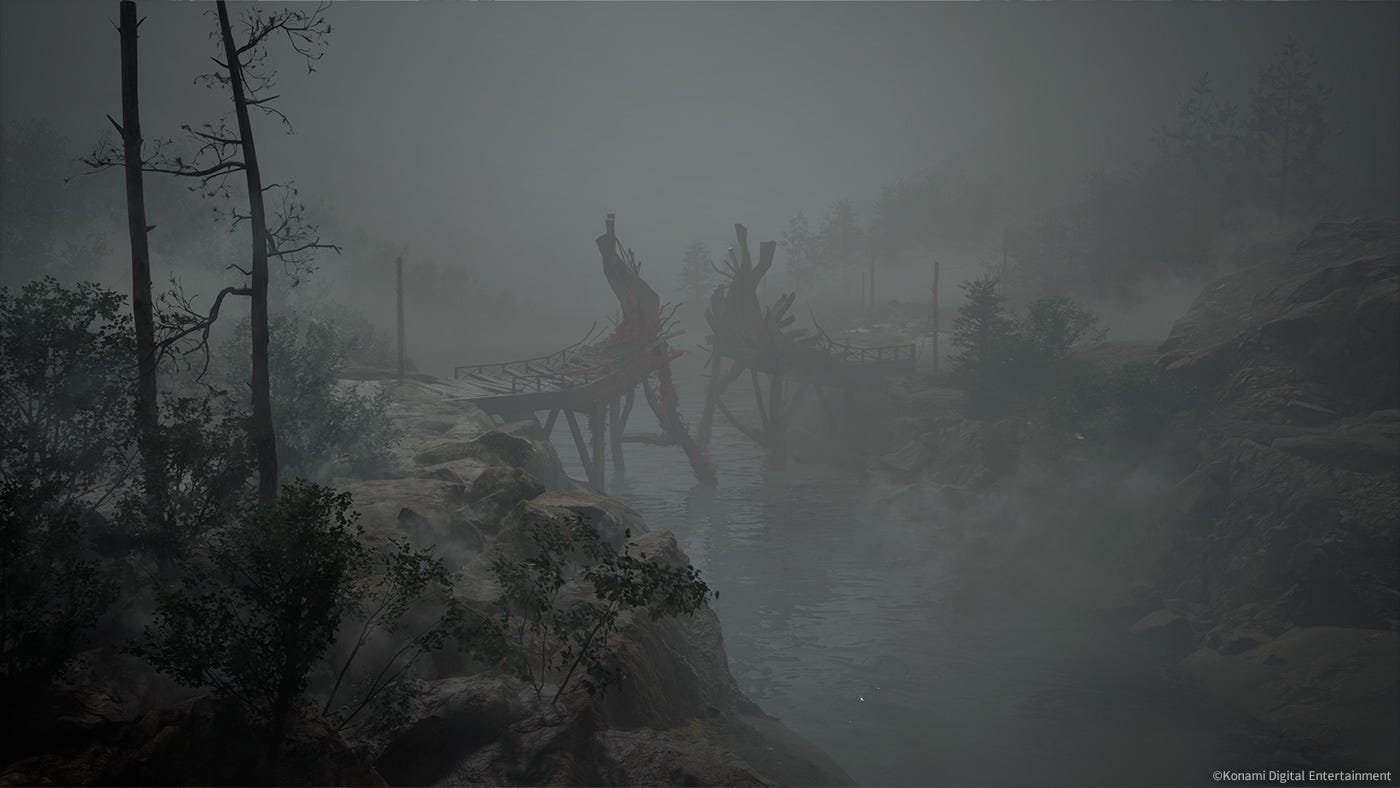

Ebisugaoka doesn’t quite have the sheer power of Silent Hill, a town that sometimes feels almost malevolent in its desire to catch people and condemn them to a twisted purgatory. Ebisugaoka, however, is very much in terminal decline and understanding why and what’s going on gives colour to Silent Hill f.

The town is rural, we know that for certain and it has suffered. Set in the 1960s, Ebisugaoka was once a mining town (the name is a reference to Ebisu, one of the seven Lucky Gods).

As I explained back in my original article, published back in May:

The town of Ebisugaoka (戎ヶ丘, えびすがおか) is timeless in its rain-slicked pathways, alleys, and stone-paved streets. The name for the town is interesting. ‘-gaoka’ means ‘on a hill’ (and the town is said to be nestled in a mountain pass; suggesting wealth from mining) but Ebisu, that’s where it gets interesting.

It’s an older kanji used in the name of a kami of fishing and one of the Seven Gods of Luck, in fact all the others are syncretic as they were adopted into Japan as auspicious but have roots in Hinduism and Buddhism. Ebisu is the only native Japanese deities in a group which otherwise serves as the patron gods of professions.

Here’s a weird thing only a geek like me remembers. One of Ebisu’s other names is Hiroku (蛭子), which is a reference to him being abandoned in a basket in the ocean. He also appears as a minor piece of lore, and has a shrine named after him, in Siren (Forbidden Siren in the West) which was directed by Toyama Keiichiro, who also directed the first Silent Hill. In that game he is a water deity associated with miscarriage as he was cast away Moses-style onto the ocean.

Oh and Ebisu also have his name to the famous beer brand too.

As a deity associated with all kinds of wealth and prosperity, it’s not surprising he lent his name to what must have once been a prosperous town.

So yes, Ebisugaoka might once have been a prosperous town with its sacred thousand-year-old tree, its rich mines and wealth but, since the war ended, the town appears to be spiralling.

Japan was broken by their surrender at the end of World War II with its people facing starvation and life being a literal fight to survive. Junko would probably have been alive just as it ended, with Hinako born a few years after (a diary entry written by Hinako’s mother suggests there is just three years between them…)

Ebisugaoka, originally known as Higa no Kuni, has its own history, along with very particular mythology around a water dragon, believed to be one of Yamata no Orochi’s eight heads that landed in what is now the town. This dragon poisoned the water and caused earthquakes, tainting the town. This is a folkloric way to explain Japan’s constant natural disasters like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and other natural disasters.

This fits in with the first note Hinako finds—dating from 1945—which talks about a poisonous geyser which infected the town with noxious gas and also feeds into the third ending, The Fox Wets Its Tail. As Shu and Hinako run through the town, the fog is revealed via radio broadcast to be the poison gas hanging over the town from an exploded geyser.

(A quick note: Japan uses two calendars, the Gregorian calendar and also the Era name. This is tied to the reign of the Emperor, so we are currently in 2025, or Reiwa 7. The Shōwa era refers to the reign of Emperor Shōwa, 1926-1989, the name given to Emperor Hirohito after his death…)

It’s here we also need to circle back and talk about religion. Ebisu was probavbly one of the initial patron kami of the town and, eventually, worship shifted to the cedar tree that now lies as a burnt husk at the Abandoned Shrine near the school.

Ebisugaoka, as a town, straddles the line between folklore and science from everything to medicine. Older folk prefer natural remedies, relying on the Iwai family; however, the Iwai family themselves are pushing for more modern methods, as well as a psychological approach and asking for the townsfolk to be educated about modern medicine. Shu himself admits that much of Hinako’s pain is psychological and him being there for her does as many help as the red capsules he prescribes her.

The Inari Faith has been the logical focus after the destruction of the sacred tree. Inari is a kami of rice and prosperity so that makes he/she/they the perfect focus point of a dying town, drowning in penury, who are known to suffer terribly from natural cataclysms every so often. By worshipping Inari, they are trying to save themselves and the town. Unfortunately, all it seems to have done is promote a kind of cult-like obsession with Inari becoming the saviour of their believers.

It’s easier to cling to folklore, if religion helps as a coping mechanism, but it has now led to a strong us/them mentality between the older and younger inhabitants of the town. When words like ‘heresy’ and ‘apostate’ start being used and people become violent, you know this isn’t Shinto, this is obsession and its dangerous.

The older residents have faith that Inari, whose land the town rests on, will save them while younger residents, like Junko and Hinako want to leave to carve new lives for themselves outside the town, as well as embracing new ideas like women being able to have lives and careers and not simply marry out.

The important thing is you cannot divorce the town, its people and its beliefs. This is why Ebisugaoka serves as more than just a setting; its endemic of a town on life support whose people will go to any length to save themselves, their families and their focus of faith. Yet these beliefs and customs are also what traps Hinako and her friends as they try to become more than the town and the families which created them.

You can read more of my Silent Hill f: Explained articles here.